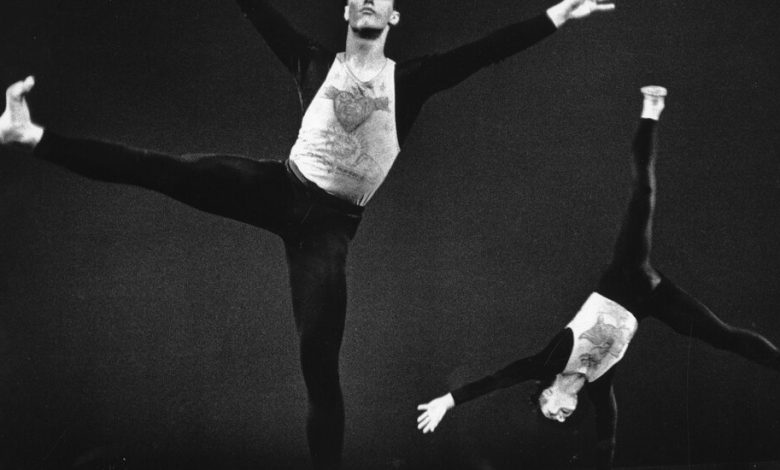

Steve Paxton, Who Found Avant-Garde Dance in the Everyday, Dies at 85

Steve Paxton, who helped radically upend ideas about dance as a member of the 1960s collective Judson Dance Theater in New York City, and who developed contact improvisation, a movement form that is now practiced around the world, died on Tuesday at his home in East Charleston, Vt. He was 85.

The death was confirmed by Lisa Nelson, his longtime collaborator and lifetime partner.

“You could say it all comes from walking,” Mr. Paxton said of his contributions to dance in a 2012 Artforum interview. At the start of his career, in the early 1960s, he was a virtuosic dancer in the companies of José Limón and Merce Cunningham, but his aesthetic curiosity soon turned to less technical, more pedestrian activities.

Inspired by experimental artists like Cunningham and the members of the Living Theater, Mr. Paxton was looking for new territory. “I was trying to find concepts that hadn’t been dealt with by these people, who we thought had already done everything,” he told the dance historian Sally Banes for her book “Terpsichore in Sneakers” (1980).

With Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs, Trisha Brown and other members of what would soon become Judson Dance Theater, Mr. Paxton took a composition class for dancers at the Cunningham studio taught by the musician and composer Robert Dunn, who adapted the assumption-questioning ideas and chance operations of the composer John Cage. In response to an assignment to create a one-minute dance, Mr. Paxton sat on a bench and ate a sandwich.

“When I wasn’t in the studio my body was just drifting along doing what it did,” he told The New York Times in 2017. “So I started to try to be more aware of what I was doing.”

His first dance, “Proxy” (1961), was made up of poses borrowed from sports photographs and basic tasks like eating a pear, drinking a glass of water — and walking. In his 1967 work “Satisfyin Lover,” he had a large group of people walk across the stage in casual clothes, occasionally stopping to stand or sit. The idea was both avant-garde and populist, breaking down the hierarchies and theatrical heightening of modern dance. It was, he later said, “about looking at what the body does.”