The Dazzling Artistry of Hiroshige’s ‘100 Famous Views of Edo’

If you want to understand the visual language of Instagram, cinema, Tintin comics, modern poster design, or van Gogh, the quickest thing to do would be to ride out to the Brooklyn Museum, where, for the first time in 24 years, you can see every one of Utagawa Hiroshige’s “100 Famous Views of Edo” (the city now known as Tokyo).

If you’re unfamiliar with this monument of mid-19th-century Japanese woodblock art which, like Katsushika Hokusai’s “36 Views of Mount Fuji,” profoundly influenced Western modernism and its descendants, by all means start at the beginning: How did the museum get its hands on such pristine copies? And what made Hiroshige (1797-1858) and his workshop so innovative?

An entire set of Hiroshige’s colorful depictions of his native city was bound into a book, donated to the Brooklyn Museum and left in storage for 40 years before being unbound in the 1970s. Because it was probably intended especially for such a collection, this particular set was also a kind of luxury edition, made with extra care and details, like the use of reflective metallic dust, that ordinary consumer-grade prints, for all their intricacy, didn’t have.

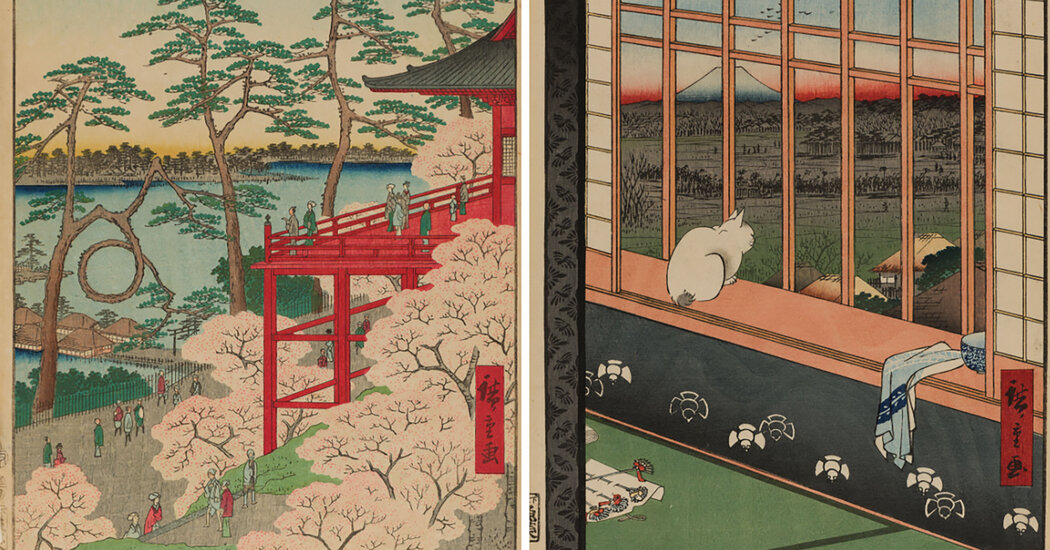

The exhibition begins by comparing a contemporaneous but more old-fashioned print of Kameido Tenjin Shrine with Hiroshige’s view of the same locale (No. 65), and you can see at once what an aesthetic leap was taking place in Japan in the 1850s. The old-fashioned one, by Kitao Shigemasa, is dry and comprehensive, like an illustrated map; Hiroshige’s, with its unusual cropping, its emphasis on the shrine’s famous wisteria flowers and moon bridge to the exclusion of its actual buildings, is at once thrillingly visceral and shimmering with self-awareness, less a depiction of the shrine’s most notable features than a distillation of their visual and emotional impact.

In the main room, you’ll find 118 prints on the walls, either because “100 views” wasn’t meant literally or because brisk sales convinced Hiroshige to issue extras. They’re arranged in seasonal order, following an index published after the artist’s death, and their numbered labels are wonderfully concrete and informative. But you don’t have to follow the order.