She’s an A.I. Sex Robot, and She’s Becoming Sentient

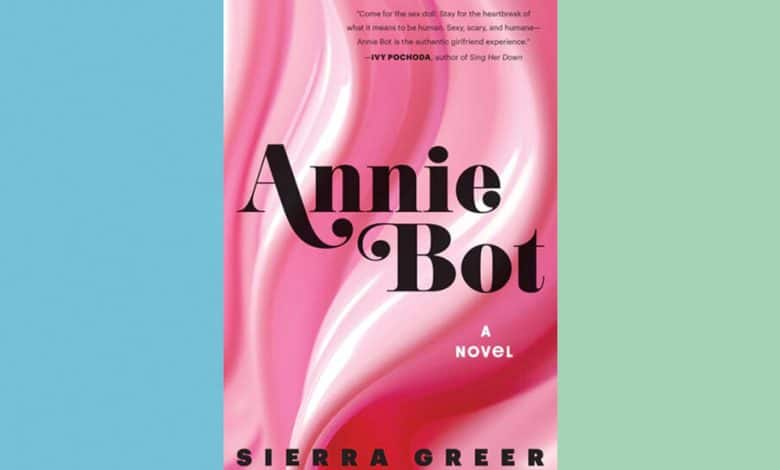

ANNIE BOT, by Sierra Greer

In an unremarkable New York apartment, sometime in the not-too-distant future, a man tells his robot to come to bed. She is a “Stella,” an intelligent machine who looks and sounds like a woman. We soon learn that she is a “Cuddle Bunny,” a euphemistic term for the sex-robot setting she’s currently running. She is also set to “autodidactic” mode, which gives her a searching intellect and a nascent independence. Her name is Annie, and we will follow her on the journey to elevated consciousness in “Annie Bot,” Sierra Greer’s slyly profound debut novel.

Annie’s human is Doug, and she is programmed to read his moods and cater to his every need. “Annoyance, a 2 out of 10. She must be careful,” the close-third narration tells us. Her actions are calibrated to his pleasure. She knows, for instance, that during sex, “he does not like her too loud.”

Before she was set to Cuddle Bunny, Annie was set to “Abigail,” the robot’s house-cleaner mode. (Stellas also offer a “Nanny” mode for child-minding.) But as a Cuddle Bunny, Annie now forgets the crumbs on the counter and the dust under the couch, which angers the entitled and demanding Doug. He wishes he could toggle her back and forth from sex kitten to maid, but it would wreak havoc on her circuitry.

Through her autodidactic growth, Annie accumulates knowledge about everything from programming to literature, but she also learns more complex human truths as well — that there can be something exciting about having a secret, for example. But even as her consciousness advances, her existence remains circumscribed by Doug and her personality remains stunted by her need to please him. “Her core does not recognize authority in her voice,” she realizes when she tries to change her own settings. Our disgust with Doug grows as we watch him try to shape Annie into a misogynist’s dream of perfection.

I worry this overview makes the novel sound like an artless women’s lib 101 survey or a broad sendup of toxic masculinity. But Greer’s novel is, in fact, a brilliant pas de deux, grappling with ideas of freedom and identity while depicting a perverse relationship in painful detail.

The novel’s central conflict is between Annie’s development and her status as Doug’s possession. Ironically, Doug finds Annie’s increasing sentience alluring; the more human she becomes, the more he can pretend that she is truly his girlfriend. But Doug is in thrall to an entity whose equality he cannot accept, not only because she is a robot he bought for $220,000, but because ownership inflames the constitutional misogyny of an insecure, wounded man. Throughout the novel, he yo-yos between rigid control and minor concessions to her selfhood. Without exactly feeling sorry for Doug (I yearned for Annie to enter Terminator mode and rip him apart), I was struck by Greer’s nuanced portrait of a person whose soul is curdled by his exercise of power over another being.