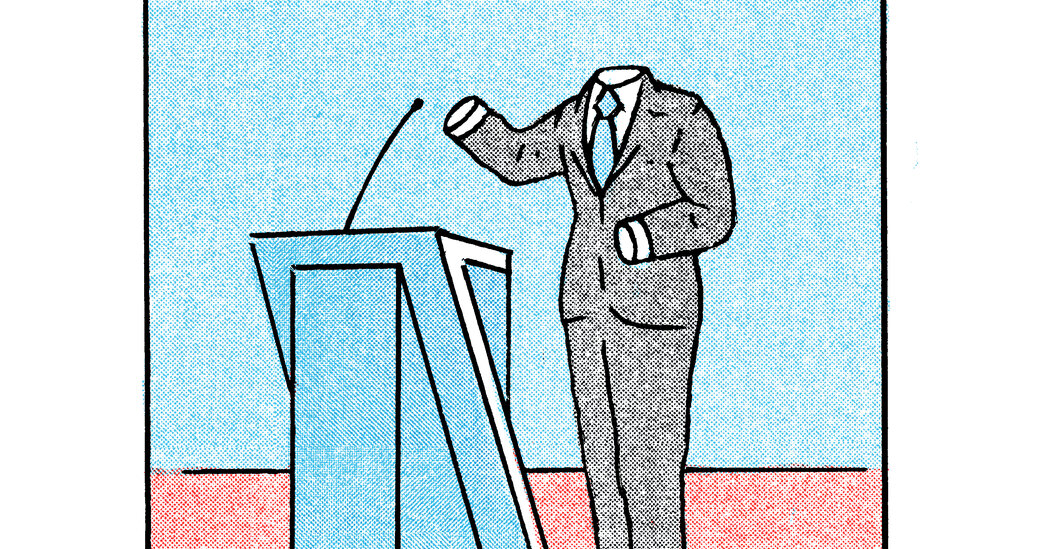

Does America Need a President?

As the belief that Joe Biden is fully equipped to be president dissolves like mist on a Delaware morning, some of his defenders have fallen back on the idea that the American presidency is not really a man but a team.

“I would take Joe Biden on his worst day at age 86 — so long as he has people around him like Avril Haines, Samantha Power, Gina Raimondo supporting him — over Donald Trump any day,” a former homeland security secretary, Jeh Johnson, said on MSNBC a few days ago. Don’t think of this as the Biden presidency, in other words; think of it as the Biden-Raimondo-Haines-Power presidency (tack on a dozen more names if you like), in which if the central pillar weakens, the support structure can still hold things up.

If you’re looking for a counter to my argument in last weekend’s column that Biden needs to be replaced because it would be incredibly dangerous to have a senescent president in the White House for the next four years (and not just because Democrats fear he might lose to Trump in November), this corporate vision of the presidency is where you need to start.

From there, you could take the relatively mild position that one lesson of both the Biden years and Trump’s first term is that the executive branch can often work around a president who isn’t quite up to the demands of the job. Or you could take the sweeping position that the government as a corporate entity almost alwaysworks independently of the occupant of the Oval Office and so an increasingly incapacitated chief executive who does what the process tells him to do would just be business as usual for the ship of state.

The mild position clearly has some truth to it: The everyday functioning of the executive branch does seem more independent of the president’s capacities than it appeared to be before January 2017. I also think the sweeping argument gets at an important reality of governmental power: Conservatives especially have long understood the limited ability of presidents to fully impose their authority on the bureaucracy they nominally lead.

But even the most sweeping version of the sweeping case still implies good reasons to regard a cognitively impaired president as a grave danger to the country. Consider the analysis of Curtis Yarvin, the noted advocate for replacing the present American republic (or the present oligarchy, he would say) with a streamlined and effective monarchy. Rolling his eyes at my column’s naïveté, he explains that in our present system the president is always and already just a figurehead:

Yarvin asks, “How does anyone even think about Washington” my way? He goes on:

Good, bracing stuff. Except that Yarvin also concedes that just occasionally, once in a great while, when the “deep state” can’t agree on policy, the president does have to make choices to resolve internal conflicts in the government — like a Magic 8 Ball being used to yield an answer, he suggests. Here’s his example of such an instance:

Interesting example, that! So the personal decisions of the president don’t matter at all, except for that time when the personal decisions of two consecutive presidents were crucial to ending America’s 20-year war in Central Asia. Just a small thing, no big deal.